I will admit it; I had to choke back tears.

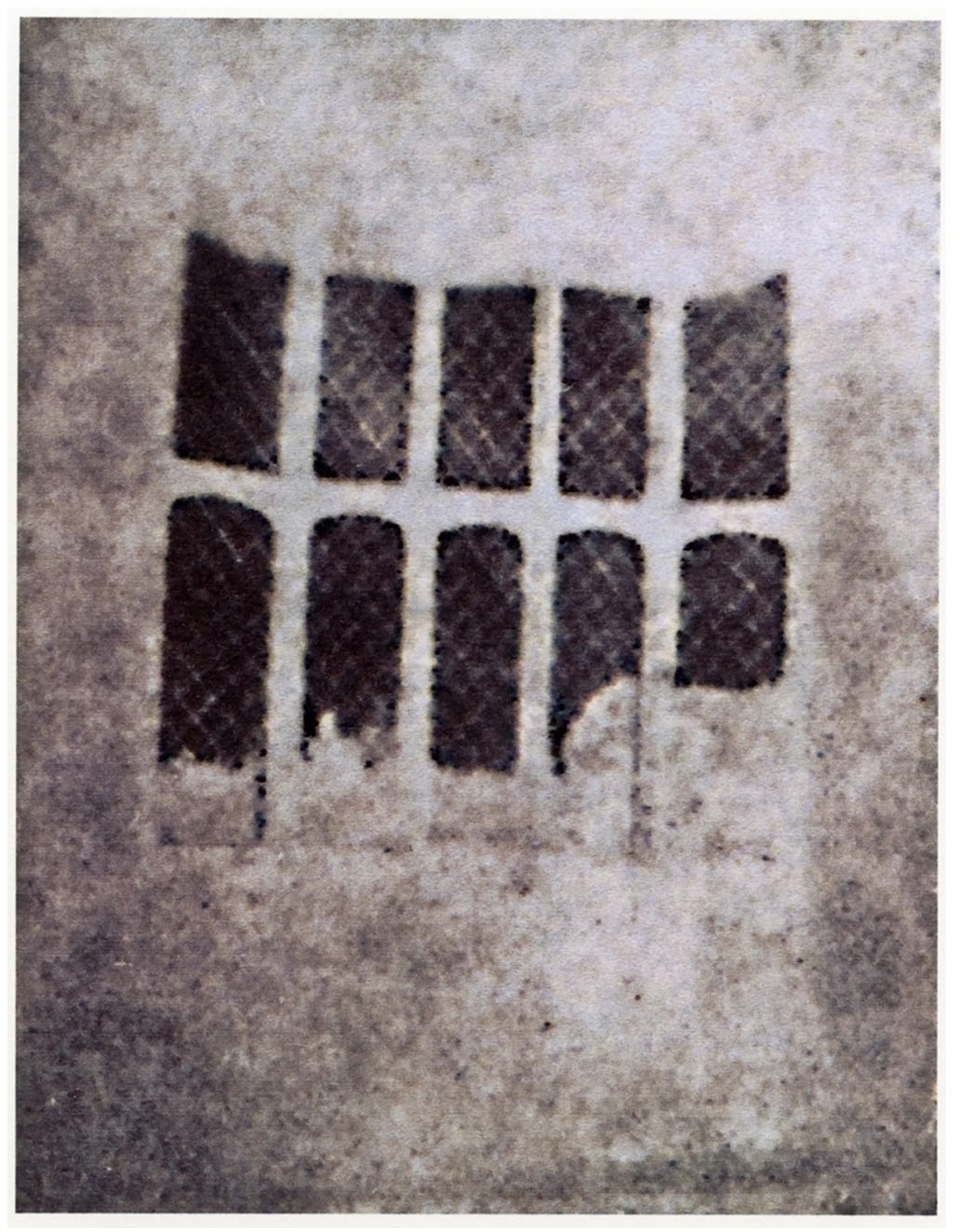

Such was my emotional response to walking around a corner and coming face-to-face with the actual location of a photograph called Latticed Window, Lacock Abbey, by William Henry Fox Talbot — what my fellow photographers often simply call The Window. It is, in effect, the place where photography as we know it began. The first successful photographic negative.

Let me back up a bit.

Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) was one of the acknowledged inventors of photography — a medium simultaneously realized in England and France in the early 19th century. Talbot’s family lived at Lacock Abbey, near the Wiltshire town of the same name. Born into wealth, Talbot was a true polymath and free to explore scientific, archaeological, and mathematical curiosities. Those pursuits eventually led him to invent the method of capturing the camera’s view as a negative image, from which multiple positive prints could be made. That negative-positive process became the basis for almost all photographic reproduction for more than 150 years.

When my job as a professor of photography with the University of Georgia’s Cortona Studies Abroad program took me to Oxford for a week, I made the journey southwest to visit Lacock. The Abbey is now part of the British National Trust and is open to the public, accompanied by a small museum that presents Talbot’s invention alongside that of his French rival, Louis Daguerre. Their processes were invented nearly simultaneously, though their outcomes were very different. Daguerre’s daguerreotypes were unique objects — luminous, almost magical — but Talbot’s negative-based process offered the possibility of reproducibility. That possibility changed everything.

After exploring the museum, I made my way to the Abbey itself. Once a 13th-century religious house, it was gradually transformed into a family home, its Gothic bones still visible beneath later additions. The rooms are layered with history, with light spilling across stone and plaster much as it did in Talbot’s day.

And then — the window.

Having taught the history of photography nearly every semester for thirty years, I knew it was there. I knew what awaited me. I’d even glimpsed it from the outside as I walked in. But nothing prepared me for standing in front of it, in the exact place where the medium that has defined my life — emotionally, intellectually, and financially — was first realized.

The latticed panes framed the view just as they had for Talbot in 1835. Outside, the lawns glowed in summer light, trees stirred in the breeze, and the geometry of the leaded glass cast its crisscross shadows on the stone walls. Making photographs there felt a bit strange; to stand where he stood, looking through the same glass, and to feel the weight and wonder of what began there.

For me, photography has always been about more than just the image on paper or screen. It is about connection — to place, to memory, to history, to other lives. At Lacock Abbey, those threads came together in a way that left me humbled and grateful. I wasn’t just looking through a window; I was looking through time itself.

Standing before that window, I felt time collapse into a single moment — Fox Talbot’s, mine, and everyone who has ever raised a camera to the world since. What he began at Lacock continues to ripple outward, connecting us across centuries. For me, it was a reminder that photography is not just a way of fixing light on paper or pixels on a screen. It’s a way of being present, of carrying memory forward, of finding ourselves at home in time.

During this challenging time, we all need to do what we can to keep our spirits up. I post my photographs and thoughts here to show that there is still beauty in the world and to promote the idea that there is grace, positivity and inclusivity in the everyday.

Throughout history, goodness most always wins, and the arts can lead the way in reflecting the good all around us. There is still light in the world.

What a fantastic connection to make. There is a reason you have always been a much beloved teacher.

What a pilgrimage it was to the birthplace of photography as we know it. Your connection to that seminal time shines through in your beautifully framed images and elegant prose.